“To will to be the true self, the self that one truly is, is the opposite of despair” – Søren Kierkegaard

Søren Kierkegaard’s ‘The Sickness Unto Death’ (1849) is one of his best-known works. In it he explores mankind’s existential problem: the struggle to exist as a unique, spiritual, self-conscious being unwilling and incapable of coming to terms with this condition, particularly under God – the creator who made him this way.

Kierkegaard describes man as a synthesis of body and soul, freedom and necessity, finite and infinite, temporal and eternal, and asserts that he is to be distinguished from beasts by virtue of possessing a spiritual nature along with the capacity to relate to his own self, that is, by possessing self-consciousness.

According to Kierkegaard this conscious self must either have constituted itself or have been constituted by something outside of itself, and the logical impossibility of self-constitution leads him to conclude that it must have been constituted by another. Thus, the true human condition, the complete human self, involves a self that relates to itself but which also relates to the Power that constituted the entire relationship.

This self is said to be constituted in such a way that it is incapable of attaining equilibrium and rest on its own. Achieving such a state requires the self to relate to the Power that created it while being willing and able to be itself while relating to its own self. According to Kierkegaard, without all of these elements being in place, the self will be in a state of despair.

This tendency towards despair stems from the uniqueness of man’s spiritual nature. The eternal dwells within him and he cannot escape it (Ecclesiastes 3:11) and it is his inability to escape from himself, even in death, that is, according to Kierkegaard, at the root of man’s despair even when he might profess to believe otherwise.

This despair expresses itself in a variety of ways. For example, when a man desires to become someone else such as Caesar and fails to do so, he despairs over himself because he did not become Caesar and therefore the self, that would have been a delight, becomes intolerable. Despair arises from the torment of being unable to become what one desires and by so doing ridding one’s self from oneself.

Another form that this takes is the despair experienced over the loss of a loved one which is in fact despair over oneself, that is, the self that would have belonged to someone else which then becomes tormenting when it has to be a self without the loved one. The self that could have been given away and seemed like riches becomes loathsome and a reminder of that which was lost.

Another expression of this struggle occurs when an individual looks to take on other selves, and in so doing seeks to rid themselves of their true self through the attainment of a better appearance, improved status, more possessions, or more desirable relationships. The expectation here is that by adopting these new selves the individual will free themselves of their true self, the self that was made for them but from which they are constantly seeking escape.

In times of despair an individual’s attempts to rid themselves of their true self can manifest as giving themselves away to someone else, perhaps in a romantic relationship or in a dysfunctional friendship, with the aim of shedding their authentic selves. In this scenario the self is outsourced to the other person and, like a reflection in a rose-tinted mirror, is taken back after passing through the validating filter of the other. When undertaking such an endeavour the individual can be said to no longer be in possession of themselves. They become empty, a void, and are thus transformed into a receptacle for the self that they want to become, the self or selves that others want them to be, or the selves that they believe are expected of them. Emptied of their true self they remain trapped in a cycle of despair, disconnected from their authentic self, and far away from dwelling transparently under the gaze of the Power that constituted them. Inevitably the inauthenticity associated with this approach becomes intolerable; the true self can no longer relate to its own self, and the individual slips back into despair.

Power and the Ultimate ‘Self’

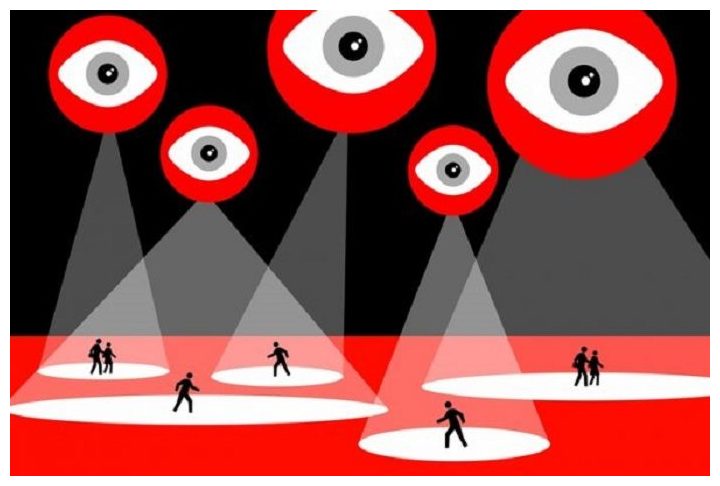

This Power Kierkegaard identifies as the God of the Bible, is exerted over humanity to the extent that individuals are prevented from escaping their true selves. This inescapable reality serves as the root cause of all existential despair and is the underlying cause of every futile attempt made to rid the self of its true self and by so doing to distance itself from dwelling under the gaze of this Power (ref. “a despairing man” ibid p281).

This is the Power that constitutes each and every self, including the self-conscious self. It is a Power more potent than death. It is an eternal power.

This aspect of the human condition remains unchanged since Adam and Eve sought out alternative selves in the Garden of Eden. After eating the forbidden fruit they made attempts to distance themselves from God by adorning their now shameful bodies with leafy disguises in an effort to become someone or something else. Such attempts at concealing the true self with the purpose of rendering it invisible to its Creator, stands in contradiction to the genuine need of the human individual to live as an authentic self in communion with God. As exemplified in the Garden of Eden, all such attempts are both feeble and futile – there is transparency whether desired or not; the true self cannot be concealed. Consequently, in Kierkegaard’s view, the individual unable or unwilling to live within this reality will suffer from the ‘sickness unto death’ referred to by Christ in Luke chapter 17, wherein “their worm dieth not” (Mark 9: 44-48).

Another aspect of pursuing the disguise of the true self and of seeking out another self is that, while the individual might choose for example to relocate geographically in an attempt to leave their troubles behind them along with the identity associated with that place, they find that these efforts fall short of what was hoped for since they are unable to leave themselves, that is their true self, behind. They cannot escape from themselves.

Humanity’s fractured relationship with God stands starkly as a feature of its disconnection from its true self—a self from which individuals desire to distance themselves due to sin. Therefore, the apparent answer for humanity in this condition is to rid themselves of themself in any way possible. However, at the root of, and simultaneously both driving and resulting from this fracture, is the on-going expression of Adam and Eve’s Garden of Eden rebellion. Humanity, in its state of chosen separation from God, imposes upon itself separation from the very source of Power that it needs to successfully negotiate the despair with which it is confronted.

Instead, in this place of despair, the individual attempts to find other ways to alleviate themselves of their condition, that is to rid themselves of themself in any way they can. Here the similarities with Adam and Eve continue in attempts to seek out alternative selves and in efforts to outwit God and avoid the imputation of sin. At its core such efforts constitute attempts to leave behind old selves, old selves associated with, and tainted by, sin.

The adoption, then, of a new self becomes an expression of the striving for and the attainment and possession of sinless perfection, thereby negating the need for the atonement of sin through Jesus Christ whose death on the cross reconciles the individual to God. In having dealt with their sin problem in their own eyes, the individual thus elevates themselves to a God-equalling status and in so doing takes on what can be considered the ultimate ‘Self’.

Of course the success of such efforts to either emulate or become another are illusory. Such perfected selves are always projected within a very carefully curated set of bounds, revealing only a fraction of the true picture to the gaze of others. Unbearable aspects of such selves, along with any despair and shame associated with them, remain concealed. The fervent dedication to the projection of a self of apparent perfection belies the reality that individuals in this condition are at the same time working very hard to rid themselves of their true self. They have sought to hide their authentic selves behind a projected fake self of apparent flawlessness.

The individual lives inescapably within community, however, the way in which they engage with and relate to that community, and the nature of the external perspective that this brings, will impact either favourably or detrimentally upon their ability to negotiate the existential dilemma with which they wrestle. Society’s atomised state deprives the individual of a crucial means of relating them self to themselves.

In humanity’s state of disconnection from God, an individual will lack the necessary external perspective to be able to relate to themselves fully. The absence of an external perspective leads either to self-isolation and a predominance of internal dialogue resulting in despair and, in some cases, depression, or else to repeated efforts to find an entity that can fulfil the role of the constituting power. This will be made manifest in certain behaviours such as in the seeking out of approval or validation from a member of the opposite sex, from peers, from a boss, or from the anonymous gaze of the general public. In this way the individual strives to satisfy their in-built urge to live transparently before an ‘other’, even if that ‘other’ is human rather than divine in nature.

Another expression of this disconnection occurs when individuals perceive either other people or objects as extensions of themselves. Instead of relating them self to themselves, they relate themselves to what is essentially an external self. Since the external entity is autonomous and therefore disinclined to cooperate to the extent that the individual’s true self would, the individual will sooner or later end up in a state of disillusionment and, ultimately, despair.

The extent to which an individual is able to come to accept their true self (and in so-doing to overcome despair), along with the way in which this process works itself out through the formation and expression of an identity consistent with the true self, helps to illuminate not only how individuals relate themselves to themself, but also how they relate themselves to the Power (or its proxy) that constituted them.

The question that remains for the individual is whether to accept the self they have been given, along with the One who brought forth this self, or else opt to pursue another self and another entity under whose gaze to live transparently, along with the despair that accompanies such a choice.

Conclusion

So, if Kierkegaard’s view of things is to be accepted, how is an individual to respond?

The first thing to be done is for the individual to seek out their true self diligently and unwaveringly and to embrace the calling to live out their lives accordingly. To accomplish this successfully will not only lead to the discovery of the unique and genuine self but will also serve as an antidote to despair. This is achieved through living life in a transparent, self-conscious, and integrated manner under the watchful eye of God. Ultimately, it entails the self taking full possession of itself. Without truly possessing themselves, the individual cannot truly comprehend their own identity, consequently embarking on an endless quest to find themselves ‘out there’, whether in reality or else, more commonly, within the realm of their own imagination.