‘When you give up your privacy, your give up your power’ – Thor Benson

Foucault (1975) describes the panopticon as a particular type of prison within which lies a central observation tower. This tower is surrounded by cells that are, or could be, under constant scrutiny from the vantage point of the central tower, and as the observer is never visible to the observed, the mere knowledge that they could be observed and their behaviour surveilled, results in adjustments of behaviour that align with the understood expectations of the party to which the observed are subject.

Foucault’s panopticon is made manifest within contemporary society in various ways such as through the presence of CCTV surveillance, the monitoring of on-line activity, the monitoring of phone calls, messages etc. And yet it is most evident and operates most powerfully, in the form of observation through the eyes of each and every citizen who has internalised that society’s prevalent norms; an increasingly atomised society that is structured in such a way as to engender a loyalty towards those in power that exceeds any loyalty towards one’s fellow citizens. In this sense, and particularly in Western society today, the panopticon is a pervasive presence.

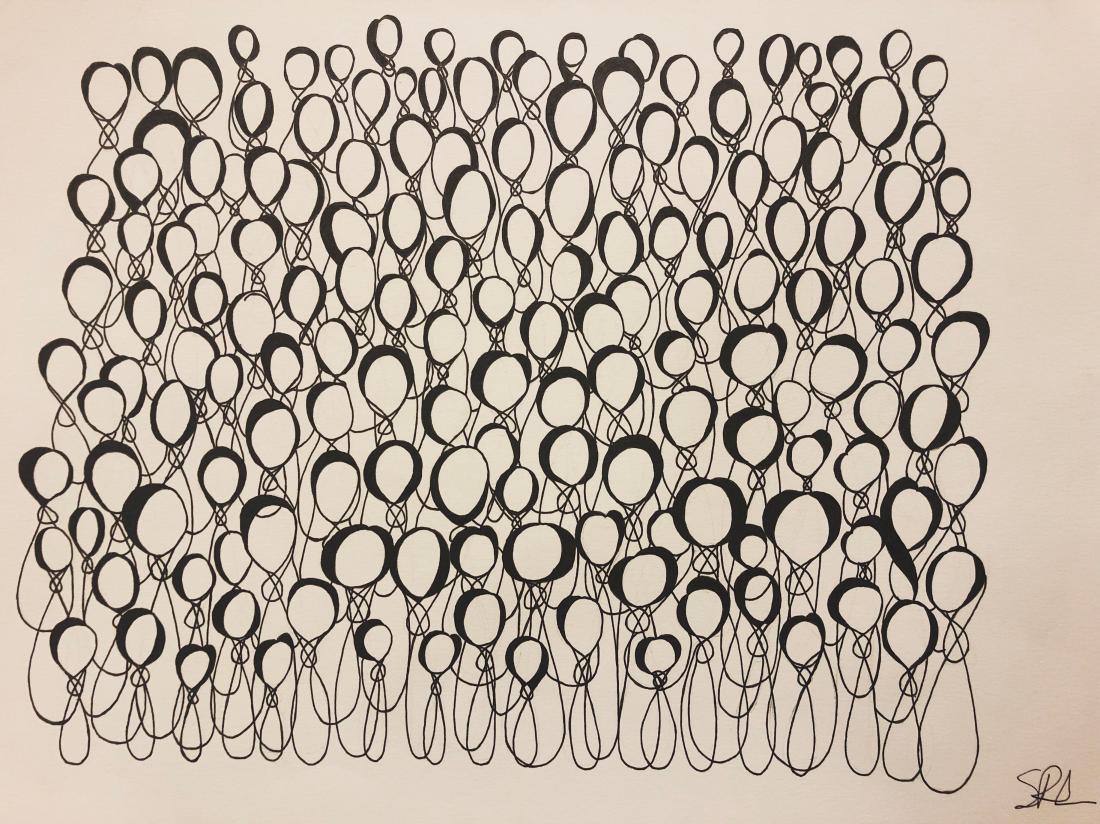

This web of observation and scrutiny from the collective other – an other acting as a programmed and efficient ensemble panopticon – leads to widespread compliance in line with those thoughts, attitudes, and behaviours that have been deemed acceptable within the society in question. Thus, the ensemble panopticon, in turning its gaze upon its own constituent parts, observes itself. That its gaze is, or could be, focused on all parts is provision enough to bring about widespread behavioural compliance in line with the expectations of those in power.

The rule of law combined with the threat of punishment serve to underpin and give teeth to the successful operation of the panopticon in its broader sense. The optic element itself is achieved through the recruitment from birth of every citizen, and the engendering within them of a willingness to give over their eyes for the purposes of the panopticon. In so doing, the interests of those responsible for its establishment are then served.

However, the question arises as to why certain behaviours are established as norms and others are not, as well as the question as to whose interests are best served within such an arrangement, and what particular form such interests take?

Furthermore, why do so-called free citizens willingly give over their bodies, their minds, and their energies to the machinery of a powerful third party, especially where there exists neither overt compulsion nor threat to do so? And why do so many individuals willingly subsume themselves within the collective – into the panoptical crowd – when to do so is detrimental both to their own and to their peers’ best interests?

Clarity on these matters is perhaps achieved by giving consideration to the crowd as entity. The individuals constituting a crowd have chosen to set aside certain identifiers of their uniqueness so as to forge a belonging within that collective. One key way in which the crowd preserves itself is achieved by ridding from its midst those elements of individuality that pose a threat to its cohesion. The individual whose uniqueness weakens the unity of the crowd must therefore either drive from himself those characteristics deemed to be undesirable, or else suffer being driven from the crowd and into social isolation.

Thus, the crowd acts as a distinct and discrete organism in possession of specific and particular impulses and drives. However, it is also observable that the crowd operates at a level that is more base than its constituent parts. The crowd, as an amalgam of individuals, fails to raise those individuals to a higher moral and intellectual state and, instead, diminishes the collective to its lowest common denominator, that is, to an animal state. The condition of the crowd, then, is animal, composed of compromised higher level individuations of humanity.

Since the crowd requires en-mass deindividuation in order to cohere, its behaviours are characteristically disinhibited as a result of the compelled stripping away of those elements that make its constituent individual members unique. Thus, the question is prompted: are the features of that which makes the individual unique and identifiable, synonymous with higher level, moral behaviours? The anonymity of the individual within the crowd leads to reduced levels of accountability, and increases the likelihood that he or she will escape punishment for immoral or illegal behaviours. Thus, it is the drive by the crowd towards deindividuation, in combination with the anonymity that the crowd provides, that brings about the threat, or indeed the actuality, of violence, chaos, destruction, and anarchy.

From here, an additional question arises as to how the true expression of humanity can best be determined? Is the concept of humanity most truly expressed in the morally superior held-to-account individual, or is it, instead, found at the base level of the anonymous, disinhibited crowd acting as a single destructive organ? Or, again, is the complete picture one of greater complexity, one in which the destructive behaviours of those individuals possessing a propensity towards evil are kept in check via the day-to-day accountability that arises out of those individuals being uniquely identifiable, but which find their full expression within the anonymity afforded by the crowd? To come to such a conclusion is to accept that most members of a society are capable of evil since, it is argued, most individuals will embrace the norms and behaviours of the crowd whenever it is in their own interests to do so.

Since the crowd provides concealment for, and strips away accountability and inhibition from, its individuated members, the internet provides an ideal context for the expression of the crowd, where a coming together in the form of the virtual mob can occur. In many contexts the virtual mob has replaced the mob on the street as the principle expression of the crowd within contemporary Westernised society.

The crowd, acting out of a base drive, is capable of retaining a unity of purpose, along with a unity within that purpose. In order to maintain its integrity, the individuals within a crowd must each tap into the same pool of common beliefs, drives, and assumptions which are, at best, only poorly articulated and seldom questioned but which are, nonetheless, known and understood within the collective. But from where does such a pool originate?

It is argued that the contents of such a pool are the expression of the core values and beliefs that form the very bedrock upon which a given society is constructed, and that those in possession of the resources necessary to fill it are, therefore, those responsible for establishing that society’s cultural, social, and religious agenda (religion here being defined as a set of beliefs and norms that interact both with the world, and with humanity’s place within it). Those same resources will be put to work to ensure that a uniform and comprehensive indoctrination programme, based upon those values and beliefs, is implemented across that entire society, being achieved covertly through the saturation of all channels of communication, education, and cultural expression. Such an approach is a proven and effective mode of societal manipulation (aka. cultural hegemony), and has been effected in one form or another within numerous societal contexts throughout history (see Gramsci, 1971).

Thus, the typical crowd in Western society (most often taking the form of the virtual mob), expresses itself out of a set of unifying base norms arrived at, neither by chance nor from an historical continuity, but as the result of a predetermined, planned, and carefully executed policy. Individuals, subject to the same common programming and drawing from the same common pool of core beliefs, values, and assumptions, will be ill-equipped to recognise the paradigm within which their entire collective operates. Those values and norms that saturate the culture and with which that society has been indoctrinated, are inarticulated givens which, on account of remaining unexpressed, also remain unquestioned; such is the effectiveness of this approach to the engineering of a culture and of a society.

These panoptical principles are most effective when they become internalised by the citizens of a society, such that they no longer modify thoughts, words, and behaviours through the instilling of a fear of negative consequences, but rather as a product of the remoulding of that citizen’s desires, wants, and preferences. The successfully programmed citizen will have developed the desire to do those things that serve the interests of those in power. He is, however, neither capable of recognising that this programming has occurred, nor that its key messages are continually being reinforced through that society’s cultural and educational channels.

Yet, the self-protective behaviours of the crowd, enacted through the meticulous elimination of elements that threaten its unity, illustrate its true fragility. This inherent instability, in combination with the time-based nature of the crowd as an ebbing and flowing accretion of individuals unified for a short time period over a particular purpose, means that the crowd must be aggressive in its self-preservation. The crowd is instilled with an innate awareness of its mortality, an awareness expressed in behaviours that belie a primal and intuitive instinct for survival.

The power of the crowd lies principally in its all-encompassing animal nature, a nature driven both by its purpose and by its aggressive drive for self-preservation. This influence has the effect both of merging those individuals who have subsumed their full selves to the will, nature, and purpose of the crowd, and of drawing in those occupying the peripheral spaces. The compliance to the will of the crowd of this peripheral sub-group will primarily be achieved through fear, namely a fear of the threat of reprisals from the crowd. Such a fear is founded, not primarily upon the threat of violence, but upon the threat of shame and of social isolation. Thus, individuals on the periphery will suppress the expression of any views that run counter to the core schema of the crowd and, in this sense, the reach and influence of the crowd extends well beyond that of the mere physical space that it occupies.

Foucault, M (1977), Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Allen Lane

Hoare, Q. and Nowell Smith, G. eds. (1971), Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci (1926-1937), International Publishers